This starting point also includes the question as

to the representative functions bestowed on the word feminism, and, knowing of the historicity of the discourse, how it can

be possible to posit a distinct feminism as an approach within a subjectively informed ethics of adequate behavior. This means

not merely negotiating contexts in the light of their preconditions and in symbolic terms, but also including already existing

arrangements within different systems and institutions in conceptual and formal decisions concerning the production of different

formats, and editing these accordingly.

This conceptual context can thus be transferred to other systems

too, which would mean that all knowledge, including knowledge of our own symbolically connoted projections, is included in

the work at hand. Perception of the format chosen in each case would be subject to adjustment, given the presence of other

formats operating within the same field. Representative proxyship and the arbitrary characteristics of conventional ascription

would be eliminated. It is the specific advantage and achievement of art to resist such unambiguous or determinate orders

and to engage critically with them. The problem here lies with the assumption as to the symbolic value of the exhibition format

itself, and the conventional belief that an exhibition can truly represent or make a case for a certain context. This assertion

is usually brought in correspondingly organized textual formats that propose contexts and ways of reading, often by drawing

on a claim to a popular relevance that is not specifically named. Here too, it would be preferable to see the structure of

exhibiting not exclusively as the result of linguistic orders of representation but rather to consider and create the exhibition

entity in itself, such that it becomes its own structuring language and content.

I believe that this would

be both possible and do justice to the field of exhibition making. Representation can and must be one of many aspects included

in work on this kind of structure. Parallel processes of reflection on representation and on subjectivity, and the materialized

decisions that emerge from these, seem to me to be an adequate method. Empathizing in this way with the structures of artistic

production means deploying control by means of a selection of already self-empowered position and claims, making use of the

specific quality of art, positing art’s speculative evidence in the service of meta-level statements, and guiding art to become

its own text in its own format.

As a consequence, the question arises as to how contemporary art production

may situate itself between historicity and self-assertion or between the negativity inscribed into it and the possibility

of speculative positivity. In particular, it seems important to me in this context to ask how far and in what form artistic

strategies make use of the popular and also operate increasingly within its contexts. Can a difference to other areas of social

production still be maintained? How far is artistic production, and at the same time the representation system of its dissemination,

a lackey of its own dialectic of innovation harnessed to market strategies? From this perspective, conceptual and dissemination

systems are always positioned within the bounds of their own indirect reality and the reality they disseminate. It is precisely

at this juncture that the inclusion and exclusion of power systems take place. I believe that awareness of all of this, and

the conceptual deployment of this awareness under the premise of a decisive assessment of all the elements available, will

lead to a qualitatively more interesting approach. The inevitably deviating concepts and formats that this engenders thus

barely seem to be vulnerable to the claims made by conventional agreements.

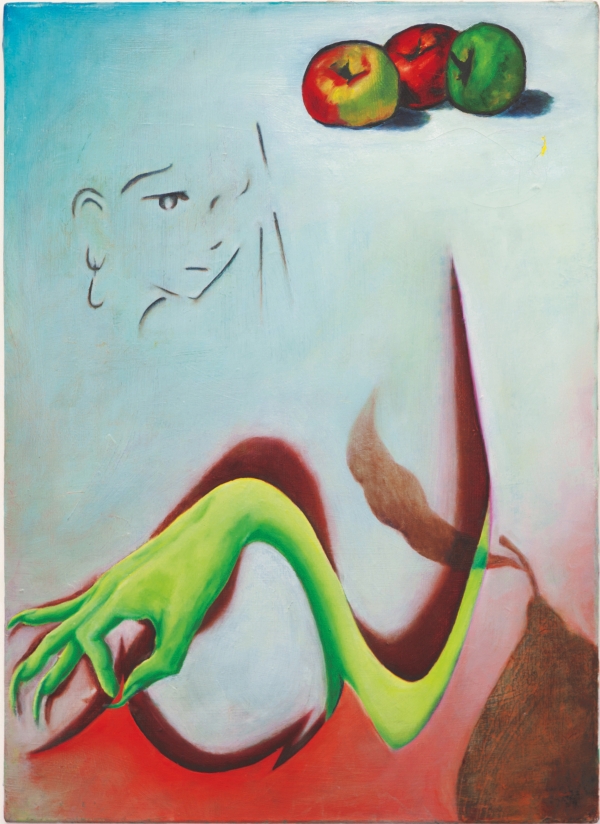

The graphic concept of this exhibition

follows this thinking, using three quotations on the invitation card, poster, and brochure. These are taken from a conversation

between Donna Haraway, Ursula K Le Guin, and James Clifford,(1) and a lecture by Ursula K Le Guin.(2) One of these quotations

provides the title of this exhibition, while the other two are presented as possible further titles in all the three formats,

although the actual title is always present. The visual graphic concept itself is based on the design of an advertisement

from the mid-1980s. The individual elements—title, image, footnote, and logo—are presented in various different ways in the

three formats. In the brochure, the short texts on the exhibited works are idiosyncratic descriptions of what we see. In some

cases, conceptual background information is withheld and in others it is provided. The style varies subtly from work to work,

and the proposed format here plays with an allegedly objectifying convention of presentation and its habitual forms of expression.

Curated & Text by Melanie Ohnemus

Photos for Download:

www.dieangewandte.at/presse (1) Donna Haraway, “Innocence is not even dreamable” and “We need more than one term for these big things,”

in

Ursula K Le Guin debate con Donna Haraway, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=59bLqzrM2r0&t=3714s. Panel discussion,

Ursula K Le Guin, Donna Haraway, and James Clifford, conference

Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, AURA: Aarhus

University Research on the Anthropocene, Aarhus, May 08, 2014.

(2) Ursula K Le Guin, “I am older than a hero ever gets,”

in Ursula K Le Guin, Avenali Chair in the Humanities, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ovZ6qgTy3SE. Avenali Chair in the Humanities

Ursula K Le Guin in conversation with Professor Michael Lucey, Townsend Center for the Humanities, University of California,

Berkeley, Berkeley, February 26, 2013.